Between 1839 and 1843, the Rebecca rioters of west Wales rode out at

night to tear down toll gates and make their protest against the high tolls

charged on the roads by the businessmen and investors who ran the Turnpike

Trusts. The rioters blacked their faces and wore women’s dresses, and they were

armed with guns and other weapons. Their visits were sometimes announced in

advance by threatening letters signed by “Becca”. Some rioters were arrested

and transported, and the unrest affected many lives.

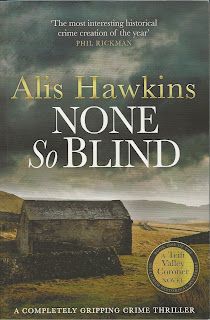

The history makes for a powerful setting for None So Blind. As Alis Hawkins explains in a historical note at the end of the novel, she has taken the story of the Rebeccas a little further by imagining that they have branched out into being a sort of moral vigilante group. It’s an idea that works really well, and even has an interesting feminist twist as at least one man gets visited for taking advantage of his female servants.

The public turmoil is matched by barrister Harry Probert-Lloyd’s private upheaval

as he comes to term with the loss of his sight. It means leaving his career in

London and returning to the life of a country squire which he had hoped to

escape. As he has to face up to his increasing blindness, he has also to face

up to the secrets of his past when a skeleton is discovered under the roots of

an old tree.

The story is told in two alternating first-person narratives, Harry’s and

his young clerk John Davies. They both know more about the victim than they

want to let on, and this gives their narratives an added depth. Concealment by

a first person narrator can be quite a difficult thing to pull off. Since we’re

privy to the characters’ thoughts, it’s easy to wonder why, if Harry or John know

something relevant to the case, they avoid fully revealing it until the plot demands

a resolution. It’s a device that can feel contrived and throw you out of the story.

Here, the fact that they are both appealing characters, combined with an

engrossing mystery, keeps the pages turning. A strong sense of place, community

and family add to the interest, especially as Harry and John clash with those

who would prefer to let the past stay in the past.

Wales, protest, attractive characters, a quest for justice and a

well-written novel: how could I not enjoy None So Blind? And so I did,

and I’ve already bought the next book in the series.

And since writing this, I’ve read the next book! In Two Minds was

as gripping and well-written as the first– so now on to the third, Those Who

Know. It’s lovely to discover a series I really like.

You might also be interested in my review of Janine Marshall Wood’s No Ordinary Convict:

A Welshman Called Rebecca (non-fiction), which tells the story of Welsh

farmer John Hughes who was transported to Australia for his part in the Rebecca riots on this blog.

Comments

Post a Comment