In Part 1 of these three articles exploring the way

in which the rail network influenced the suffrage campaign, I looked at how

trains were instrumental in facilitating suffrage campaigns, including militant

activism, as well as enabling suffrage organisations to set up and run their

national networks. I also explored the way that trains became arenas for

sometimes violent encounters between suffragettes and politicians. You can read "Cheap and Easy Railway Traffic: Suffrage and the Railways Part 1 here.

The second part described how the Glasgow to London

train became the focus of a struggle with the police when suffragettes

attempted to rescue Mrs Pankhurst on her way to Holloway Gaol. You can read "Cheap and Easy Railway" Traffic Part 2: The Battle to Free Mrs Pankhurst here.

In Part 3, I take a look at how trains and railway

stations were themselves targets of suffragette militancy.

In March 1913, Hugh Franklin, who we met in Part 1 when

he assaulted Winston Churchill on a train in 1910, was sent to prison for nine

months for setting fire to a carriage at Harrow Station the previous October. In

April an explosion blew out doors and windows at Oxted Station. In the same

month a carriage was wrecked by an explosion at Stockport and another at a

siding in Cricklewood. Three compartments of a train at Teddington were destroyed

by fire and others damaged.

In May, a bomb containing nitro-glycerine was

discovered in an empty third class carriage of a passenger train which had

recently left Waterloo at Kingston. The fuse had been lit but had fizzled out. Attached

to the device was a note saying, “Lloyd George is a rotter”. Another apparently

read, “Give us votes and we will be contempt” (sic). In the same month, there was

a bomb hoax at Macclesfield railway station. A fire was started at South

Bromley Station, but extinguished before the Fire Brigade arrived.

In July there was an arson attempt at Shields Road

Station in Glasgow, when fires were started in two ladies’ waiting rooms, and timber

in a railway goods yard at Nottingham was destroyed by fire. In September,

Kenton Station, Newcastle, was destroyed. A note was found nearby which said, “Asquith

is responsible for militancy. Apply to him for damage”. A few weeks later there

was an attempt to burn down Heaton station, also in Newcastle. In October 1913,

there were fires at Hadley Road and Northfield Stations in Birmingham, and at Oldbury

Station where a note was left saying “Militancy will go on.” In November there was

an arson attempt at Streatham Hill, when petrol was used to light a fire in the

booking hall. Another Birmingham station, Newton Road, was also set alight, as

was Castle Bromwich station.

In addition, railway telegraph wires were cut in a

number of locations. The London Underground was targeted too. A parcel

containing nitro-glycerine was found at Piccadilly Tube Station in May 1913.

|

| Emmeline Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick Lawrence and others, 1911. While suffragettes attacked the railways, they still relied on them for their campaign. |

The railway attacks continued into 1914. At

Porthcawl the words “Votes for Women. You cannot govern women without their

consent” were discovered scratched on a carriage window. There was a fire at

Wigan Station in February and at Bangor Station in April. In June a bomb was

found in a goods train at Wellingborough. In July 1914 the Morning Post,

cataloguing suffragette militancy since 1913, cited ten arson attempts on

railway carriages.

At the same time as the arson attacks were being

carried out, some suffragettes were raising funds with collections or sweet

sales outside railway and tube stations. You can’t help wondering how popular

these were with commuters. Inevitably, the WSPU blamed any hostility on the

British press and lauded the courage of women standing outside railway

stations, as well as in other public places, “not knowing what they may have to

face at any moment owing to the incitement of the Press to hooligans to attack

them” (The Suffragette, 7 March 1913). The WSPU also launched a poster

campaign at railway stations aimed at increasing sales of The Suffragette.

Surprisingly, these were displayed at many stations.

It must be borne in mind that suffragettes were

blamed for almost any act of vandalism during this period. For example, when cushions

were slashed in a railway carriage on the Chatham line in February 1913,

militants were said to be responsible. A month later, cushions were slashed on

the North Eastern and North British Railways and labels saying “Votes for

Women” were stuck to them. The presence of such labels was not always conclusive

proof that suffragettes had left them.

Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that some at

least of the attacks were carried out by suffragettes. As we saw in the case of

Hugh Franklin, the police were able to bring charges in a few cases, though not

all stuck. When Mr and Mrs Baines, their son, and local WSPU secretary Kate

Wallwork of Manchester were charged with causing an explosion in a carriage at

Heaton Railway Station, Miss Wallwork and the men were acquitted, and Mrs

Baines absconded while on bail. In most cases, however, it seems those

responsible were never discovered.

The WSPU leaders also implicitly claimed

responsibility for some of the incidents. At a speech at the London Pavilion in

March 1913, Annie Kenney noted the

arrest of five women “for the constitutional action of trying to present a petition

while the women who burnt down the railway station have got off

scot-free” (The Suffragette, 14 March 1913). On the other hand, although

many of these attacks were reported in the pages of The Suffragette, it was

often with the comment that they were “supposed” to be the work of suffragettes.

The WSPU leadership did not always know what its followers were doing, but they

always defended their right to do it.

Confusingly, too, in June 1913 the WSPU issued a

statement denying involvement in an attempt to wreck the London to Plymouth

express saying that it “would be contrary to the policy of the Union”. They

added that “no interference with the railway system is sanctioned by the WSPU”

(The Suffragette 27 June 1913). This is presumably a reference to the policy

that no life should be endangered by militancy.

In spite of the WSPU’s protestations, the public can

hardly be blamed for fearing injury or death might be the result when people planted

bombs on trains. Travellers could not have been reassured by the Aisgill tragedy

in September 1913, when fourteen passengers died, many after being trapped in

burning carriages, after two Scottish express trains collided. Their confidence

could not have been restored by the publication a few days later of a report

that there had been a rise in the number of fatalities and deaths on the

railways since the previous year.

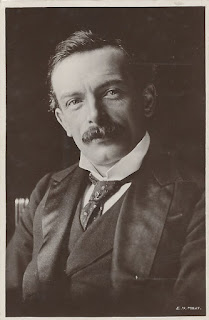

|

| David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer |

On 23 October 1913, David Lloyd George, Chancellor

of the Exchequer, speaking in Swindon, commented, “It is no good burning down churches, pavilions, and railway

sidings, and menacing the lives of poor workmen, who after all are not

responsible for the present condition of things. You don’t gain anything by

that” (Manchester Courier, 24 October 1913). Whether or not suffragette militancy

did more harm than good to the women’s suffrage campaign is still as fiercely debated

today as it was during the militant campaign. Nevertheless, suffragettes continued both

to destroy railway property, and to rely on the smooth running of the railway

network, to the end of their campaign in August 1914.

Picture Credits: Emmeline Pankhurst, Emmeline

Pethick Lawrence and Others, 1911, Women’s Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright

Restrictions

David Lloyd George Postcard – author’s private

collection.

“Women and Transport: Historical Perspectives”

Circumstances permitting, later this year the West of England and

South Wales Women’s History Network Annual Conference will be looking at more

aspects of women and transport. “Women and Transport: Historical Perspectives”

will take place on Saturday 3 October 2020 from 10 am to 5pm at Central

Community Centre, Emlyn Square, Swindon SN1 5BL. Deadline for Call for Papers

is 24 April 2020. For further information see the WESWWHN website.

Sign up for my newsletter here and receive a free copy of The Road to Representation: Essays on the Women's Suffrage Campaign (ebook)

Comments

Post a Comment