In February 1912 the Bristol Liberal MP Charles E H

Hobhouse addressed a meeting of the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage

in the city’s Colston Hall. During his speech he remarked, “In the present days

of cheap and easy railway traffic they [the suffragettes] could always arrange

numerous deputations or demonstrations and they could be as noisy as their

funds permitted – (laughter)…” (Western Daily Press, 17 February 1912).

Hobhouse was anti-women’s suffrage and remained so even

after the passage of the 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote to

some British women. Although he had no understanding of or sympathy with the

suffrage movement, his statement does show that he understood one thing: the

importance of the rail network to the suffrage movement. In this three-part

article, I’ll be exploring the connections between the railway system and the

suffrage campaign, particularly the militant campaign.

Both militant and non-militant women’s franchise campaigners

relied on train transport. Trains, as Hobhouse noted, took protesters to demonstrations

and deputations. On 13 June 1908, for example, special trains to London were

put on all over the country to allow women to travel to join a march from the

Embankment to the Albert Hall organised by the non-militant National Union of

Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). A week later, thirty extra trains were

provided to carry suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU)

to a demonstration in Hyde Park that attracted over 250,000 people.

|

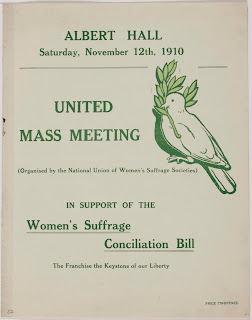

| Supporters travelled by train to take part in demonstrations. This one at London's Albert Hall was organised by the non-militant NUWSS. |

During by elections, both militant and non-militant suffrage

workers descended on contested constituencies to campaign for women’s suffrage.

Militant protestors also travelled to and from London to join the great WSPU deputations

to the House of Commons whenever a suffrage bill was debated – and invariably

defeated. The militants used the rail network to facilitate their more disruptive

acts too. When suffragettes interrupted a speech by the Prime Minister, H H

Asquith, at Bletchley Park in August 1909, they went by train to Leighton

Buzzard and walked to the Park from the station. Probably the most famous rail journey

made with militancy in mind was that taken from London Victoria to Epsom by

Emily Wilding Davison when she went to the 1913 Derby. Days later she died of

her injuries after running out in front of the King’s horse.

|

| Emily Wilding Davison's return train ticket. |

Suffragettes could also use the trains to make their

campaign visible. When Lillian Dove Willcox and Mary Allen were released from

Holloway and returned to Bristol they were met at Temple Meads Railway station

by a procession of women wearing suffragette colours and carrying banners. From

here, the two suffragette heroines were driven in decorated carriages through

the centre of the town to a welcome reception.

Large national organisations with their headquarters

in London relied on being able to move people easily and quickly around the

country in order to function. Suffrage campaigners attended meetings large and

small: Winifred Coombe Tennant often caught the train from her home in Neath,

South Wales to go to London meetings of the national executive of the National Union

of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Suffrage workers travelled throughout the kingdom

setting up and running a network of local branches, and organising

demonstrations, events, fund raising, and talks at local level. Campaigners

moved around the country as they were needed, supporting local organisers when

required. When Winston Churchill visited Bristol in 1909, workers were deployed

from London and Exeter to help Bristol and West of England WSPU organiser Annie

Kenney arrange a number of protests.

The railway system played a large part in propaganda

work too. Not only did it enable the distribution of suffrage publications such

as Votes for Women or The Common Cause, it also meant that

workers were able to spread their message widely. Popular speakers used trains

to facilitate their speaking tours. Trainers from head office travelled to the

provinces to instruct local branch members in public speaking and other aspects

of suffrage work. The movement’s celebrities were a tremendous boost to the

cause. A visit by Mrs Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

and other well-known figures brought publicity, new members, and much-needed

cash.

|

| Emmeline Pankhurst and Lady Constance Lytton, popular WSPU speakers, at Waterloo in 1910. |

Travelling around organising, speaking and

protesting was a life that took its toll on the women involved. In 1909 WSPU

member Millicent Browne, whose biography I am writing, was sent to campaign in

North Wales. She had a terrible journey: she was suffering from appalling

period pains, no one met her at the station, she had nowhere to spend the night

and all the boarding houses she tried were full. Eventually she managed to

obtain a reviving glass of hot water and gin, and one of the landladies let her

sleep in an armchair.

Kate Parry Frye worked for the New Constitutional

Society for Women’s Suffrage, which was founded in 1910 and positioned itself

between the WSPU and NUWSS by advocating anti-government action but eschewing

WSPU-style militancy. The diary she kept throughout those campaigning years is

full of references to train travel, and amply illustrates how much campaigners

relied on the network. It also shows how the constant travelling, often at

short notice, contributed to the exhaustion, discomfort and difficulties the

peripatetic campaigner endured. The stress of illness, homesickness, bad food, and

comfortless lodgings were compounded by rushing to catch trains, over-crowded carriages,

and having to lug bags around or entrust them to left luggage offices.

In 1911, Kate Parry Frye travelled to the Women’s

Coronation Procession in London. There were, she wrote, “So many people

travelling…at Norwich, where I had to change, it was quite a pandemonium, and

so hot. The train was half an hour late” (Campaigning for the Vote: Kate

Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary, ed. Elizabeth Crawford, Francis Boutle

Publishers, 2013, p 66). On a later journey, “I lost my luggage. Two porters

were very rude…I told an official I had been travelling since the early morning

and had come to the conclusion that the Railway companies made it as difficult

as possible for people” (Diary, p 71). By 1913 it had all become too

much for her. After a journey to Dover she declared, “I simply cannot bear

these journeys and arrival in places. And such a pouring wet night and such a

filthy station” (Diary, p 137).

While trains were valuable resources enabling the

carrying out of militant and non-militant campaigns, the administration of

organisations, and the dissemination of the suffrage message, they were also sites

of activism for the militants. In 1907 Mary Gawthorpe and Annie Kenney were

invited to the Riviera by Emmeline and Frederick Pethick Lawrence for a holiday.

They found themselves travelling on the same train to Cannes as the prime

minister, Henry Campbell Bannerman, when they went into the dining car for tea.

They immediately seized on the opportunity to talk Votes for Women to him and

plonked themselves down beside him. “The dear old man”, as Mary Gawthorpe

called him, was puzzled put polite, though when they told him who they were he refused

to be drawn on the issue. He would only advise, “You should adopt different tactics”

(The Guardian, 3 April 1907).

Trains were also good places for deliberately

tracking down VIPs. In March 1909 Bristol Liberal MP Augustine Birrell was approached

at Bristol Temple Meads Railway Station by suffragettes Elsie Howey and Vera

Wentworth. He refused to speak to them. John Redmond, MP, had two bags of flour

thrown at him by a suffragette on a train to Newcastle in November 1913.

In 1912 King George visited Bristol to open the King

Edward VII Memorial Infirmary, named after his father. The home secretary, Reginald

McKenna, accompanied him. McKenna was accosted by Helen Cragg when he got down

from the King’s carriage at Llandaff. She jumped over a wall, ran towards him, grabbed

his arm, and was immediately arrested. The King and Queen were standing only a

few feet away.

Helen Cragg later told the arresting officers that McKenna

should not have been “jaunting about the country while women were starving in prison”

(Bristol Times and Mirror, 27 June 1912). In Bristol, Miss Billings, who

was waiting for the royal carriage, was recognised and prevented from carrying

out any protest by being detained in one of the station offices until the end

of the King’s visit, when she was put on a train back to London.

The speed with which the police pounced on Helen

Craggs and others is understandable given that these encounters often

degenerated into violence. When Winston Churchill visited Bristol in 1909 he

was attacked at Temple Meads Railway Station by Leeds suffragette Theresa

Garnett. She broke through the cordon of detectives surrounding him and lunged

at him with a whip crying, “Take that you brute!” In 1910 Churchill was assaulted

in a train travelling to London from Bradford by male supporter, Hugh Franklin.

In 1912 Emily Wilding Davison whipped a clergyman at

Aberdeen station, having mistaken him for Lloyd George. In 1914 Lord Weardale,

a joint president of the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage, was also assaulted

with a whip at Euston station having been mistaken for the prime minister, H H

Asquith. He was struck on the back of his head, fell to the ground, and was

repeatedly hit. His wife, Lady Weardale, was also struck during the scuffle.

Asquith had several violent encounters with

suffragettes, many of which occurred at railway stations or on board trains. In

1910 he was greeted at Burnley station by what his daughter Violet called a

“Suffragette mêlée” (Mark Bonham Carter and Mark Pottle, eds, Lantern

Slides: The Diaries and Letters of Violent Bonham Carter 1904-1914,

Phoenix, 1996, p 223). After a crossing from Boulogne in 1912, Violet reported

that her father was “abordéed by a Suffragette…At Charing Cross…a horrible mêlée

with Suffragettes ensued – I had the pleasure of giving one an ugly

wrist-twist!” (Lantern Slides, p 304). In April 1914 while he was travelling

to his East Fife constituency, a woman jumped on the footboard at the front of

his carriage and threw a letter protesting about forcible feeding through the

window. She was still clinging to the train when it set off, but a railway police

officer pulled her off. On the prime minister’s return journey from Cupar, two

women jumped off the opposite platform, ran across the lines, and scrambled up

to shout “woman torturer!” at him.

Find out in Part 2 about the battle to free Mrs Pankhurst on the Glasgow to London train following her arrest in 1914. Part 2 will be published on Tuesday 14 April 2020.

Picture Credits: All images Women’s Library on

Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

“Women and Transport: Historical

Perspectives”

Circumstances permitting, the West of England and

South Wales Women’s History Network Annual Conference will be looking at more

aspects of women and transport. “Women and Transport: Historical Perspectives”

will take place on Saturday 3 October 2020 from 10 am to 5pm at Central

Community Centre, Emlyn Square, Swindon SN1 5BL. Deadline for Call for Papers

is 24 April 2020. For further information see the WESWWHN website.

Read Elizabeth Crawford's fascinating blog – 'Emily Wilding Davison And

That Return Ticket' – at https://womanandhersphere.com/2013/05/27/suffrage-stories-emily-wilding-davison-and-that-return-ticket/

|

The Bristol Suffragettes available in paperback from Amazon UK and SilverWood Books. For other buying links and further information see my website.

Sign up for my newsletter here and receive a free copy of The Road to Representation: Essays on the Women's Suffrage Campaign (ebook)

Comments

Post a Comment