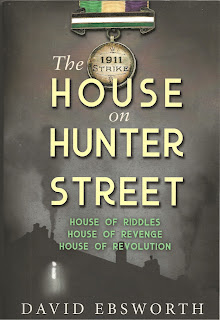

I was particularly delighted to receive my copy of The House on Hunter

Street from David Ebsworth because I’d seen an early draft of the novel and

we’d discussed aspects of the women’s suffrage movement. While I don’t believe

there’s a “right” or “wrong” way to tell the history, it is more complex than

many people realise and there’s often a tendency to cling to simplistic

interpretations. For example, the idea that the suffragettes won the vote for

women is a very popular way of presenting the campaign, but it’s very far from

telling the full story or being the only narrative that deserves to be heard.

The House on Hunter Street brings alive

one of those perhaps lesser-known narratives of the suffrage movement by

focussing on the perspective of a working-class woman, Cari Maddox, and linking

the women’s campaign with the struggles of the labour movement. Cari’s story is

told against a backdrop of the 1911 dockers’ strikes in Liverpool, which in its

turn brings in racial inequalities through the involvement of African seamen. At

the same time, women’s rights, labour rights and black people’s rights don’t

always go hand in hand, and the book captures those complexities. Thrown into

the mix are religious tensions between protestants and Catholics, and there’s also

a keen interest in the immigrant experience: the Welsh Maddoxs live alongside

Irish, African and German immigrants.

This is a Liverpool of troubles and tensions, which often erupt into violence. It’s how this setting affects the characters that makes for an absorbing story. Cari and her family face their trials and tribulations, have their love affairs, their secrets, and fall out with one another, lending elements of family saga to the tale. I really liked Cari; she’s a strong woman amongst a cast of strong and vivid characters, and her faith in family is touching. Her belief – and desire – that families stick together (they “close ranks around each other – no matter what may come of it”) is an important aspect of her character. It is one that is tested by her brother who offends his father by falling in love with a “Papist”, and a sister hiding from the police after a theft at her workplace.

|

| The non-militant suffrage campaigners' premises in Liverpool |

Cari really comes into her own when her family is threatened by one of

the most deranged, scene-chewing villains I’ve come across in a long time. Tom

Priddy is sinister, vengeful, sly and insinuating, and his wicked machinations

are a joy to behold. He’s a baddie deserving of the worst kind of come-uppance.

Does he get it? No spoilers here!

All in all, The House on Hunter Street is a powerful, forthright novel.

Dave’s personal links to the story are explained in the useful Historical Notes

at the end of the book, which increase the sense of a story written with

passion and commitment. My only quibble is that though the structure – the

focus on a single year, 1911 – works very well, it meant I didn’t get the rest

of Cari’s story!

An enjoyable and absorbing read.

Picture Credits:

Liverpool branch of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies - Women's Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Comments

Post a Comment