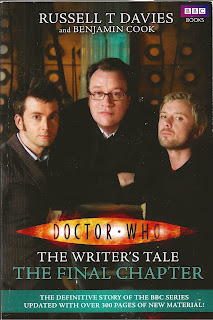

The Writer’s Tale: The Final Chapter, Russell

T Davies with Benjamin Cook (BBC Books, 2010)

I read a lot of books about writing and creativity. I think, though, they

are two different things. Books about writing are about the nuts and bolts – how

tos and guides. Books about creativity are explorations of what creativity is, how

and why we create books or art or whatever we create, how creativity happens or

how we make it happen, what it means, what it does. I love all the different approaches

there are to creativity, the variety of experience, reading a book and thinking

“yes it’s like that for me” or “no it isn’t like that”, and knowing that both

the yes and the no are wonderful and intriguing and inspiring.

Russell T Davies doesn’t like books about writing. He tried to read Story by Robert McKee once but it scared him so much he only managed a paragraph. It wasn’t that he disagreed with the book, rather that he didn’t want “some tutor’s voice intruding into my head”. He wanted to think things out for himself rather “than be taught about it”.

Unlike Davies, I think books like Story can be useful. But I think

he’s got a point. I think it’s wise to approach the guides and the how tos with

caution. What puts me on the alert is when someone declares that their way is

how you “should” write. Sometimes it’s merely implicit in the bossy tone, or

the hints of inevitable failure for those who don’t accept the author’s version

of reality, or the assumptions that there is only one model for being a

successful writer.

The Writer’s Tale is a book about creativity,

although you could also pick up some tips from it about writing – for example,

how to construct a story. But that would be by seeing a writer in action in

specific situations, rather than being told in general terms “this is how”. As

Davies says, he’s “wary of anyone who’s about to start writing ever reading

something like this and thinking, that’s the way to do it, that’s what I

must do”. He adds that he doesn’t “think the creative process copies too

much anyway. I think it finds its own way”.

Davies is open about the way he works, he’s willing to tell all – to

answer a question about lying (“isn’t writing one big fat lie?”) for

example – but he never once says “this is how it ought to be done”. Perhaps it’s

because of the form the book takes. It’s basically an edited email exchange between

him and Benjamin Cook, and for that very reason it can’t solidify into bullet

points and “top ten tips”. It’s all over the place, Davies zips from topic to

topic, he goes to Tesco’s, fancies the barista in his local coffee shop, the

letter a on his keybard flls off. Of course, he knew when he wrote his

emails they were intended for publication, but there’s still a sense of honesty

and immediacy about them, that this is what he really thinks, this is how he writes

(his ideas come from an ideas shop in Abergavenny), these are the mistakes he’s

made, these are his doubts, this is how he feels about success, money, fame.

Maybe it is all one big fat lie. I don’t think so, but even if it is,

it’s an entertaining one. It feels like you’re eavesdropping on a real conversation,

as if you’re in a café and two people on the next table are discussing their

private lives and you don’t want to miss a word. That can make it a bit cringy

too sometimes: Benjamin Cook’s frequent “you’re brilliant” for instance should perhaps

have been kept between the two of them. Of course, everyone wants to hear “you’re

brilliant”, but to us eavesdroppers it sounds a bit – well – sycophantic. And

all the fan boy stuff and whittering on about people’s arses gets a bit

tedious.

But I thoroughly enjoyed the book. It’s behind-the-scenes-stuff about Dr

Who, for goodness’ sake. And though I’ve never written a television script

and have no plans to, I think Davies has got some fascinating things to say

about creativity. I suppose if you hate Dr Who you wouldn’t read The

Writer’s Tale, let alone get much out of it, but as Davies says, it’s “whatever

works for you”.

I also read…

Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Lisa See (Bloomsbury,

2007)

Lisa See’s book about the lives of women in nineteenth-century China is a marvel. It follows two friends, Snow Flower and Lily, as they prepare for adulthood. That means learning how to be obedient to – just about everybody: parents, elders, husbands, mothers-in-law, sons; having their feet bound; learning how to run a household. In a strictly regulated world, how are they to have any kind of private or inner life? They do it by learning nu shu, a form of women’s writing which enables the two women to share news and express feelings and opinions that must otherwise be silenced.

It's a beautifully written exploration of how, even in the most confined

setting, women carve out a life for themselves – even if that life is not

always a happy one.

Comments

Post a Comment