I recently re-read Helen Margaret Nightingale’s suffrage play, A

Change of Tenant. The play was often performed at meetings and fund raisers

by suffrage societies, and was also produced by professional members of the

Actresses’ Franchise League. Little seemed to be known about Helen Margaret Nightingale,

as Susan Croft notes in Votes for Women and Other Plays (Auroro Metro

Press, 2009), which includes the text of the play. However, from the few details

Susan Croft provided I was able to discover more about Helen’s life.

Helen Margaret Nightingale was born in 1883 in Banbury, Oxfordshire. Her

father, Charles Frederick Nightingale (1846-1904) was the minister of the

Wesleyan chapel in Marlborough Road (still in use as a Methodist church today).

Charles Nightingale, who was born in Manchester, began his career in the church

in 1865. He had worked in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Bradford, Sheffield, Leamington,

Bolton and Torquay before moving to Banbury in 1881. In 1884 he moved to Wolverhampton,

and in 1887 to London, serving first at Highbury, then Stoke Newington, Stratford,

and finally Wandsworth, where he died in May 1904.

Helen’s mother was Ellen Emma, née Bayliss, born 1854 in Wolverhampton. She

and Charles Nightingale married in Torquay in 1879, where Charles was minister

at Union Street Chapel. Helen was the eldest child: her sister Edith Annie was

born in Wolverhampton in 1885; her brother Frederick Bayliss in London (Highbury)

in 1889; and Elsie Mary in Stoke Newington in 1894.

Helen was thirteen when the family moved to Wandsworth. They lived at 47 West Side, Wandsworth Common. Helen lived all her life there. In 1906, aged twenty three, she published her novel, Savile Gilchrist MD. It was fairly well received, and thought to promise well for the future of the young writer.

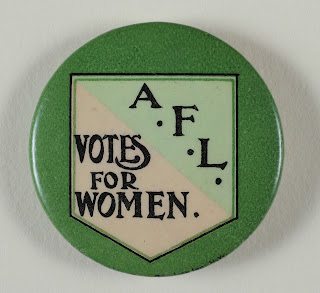

Actresses' Franchise League Badge. The AFL toured A Change of Tenant in 1910.

A Change of Tenant followed in 1908. In

October 1908, it was performed at a “conversazione” by the Wandsworth branch of

the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. Over the next few years it was performed

by other suffrage groups in Bradford, Hayward’s Heath, Leeds and elsewhere, and

it was also produced by the Hammersmith Ethical Society. The play was published

by the Woman Citizen Publishing Society in 1909.

As well as supporting the cause of votes for women with her drama, Helen

Nightingale wrote articles and stories for suffrage publications The

Franchise and Common Cause. Later, she corresponded with Common

Cause in 1921 on the issue of birth control, arguing that working class

women, overburdened by frequent child bearing, should be taught birth control

methods. “And have not mothers,” she wrote, “as much right as miners to a

higher standard of living and greater liberty and leisure?” (Common Cause,

29 April 1921). She also wrote for The Englishwoman.

Other work included The Choir at Newcommon Road published in 1909. This was only about sixty pages long so possibly it is another play or short story, although I have been unable to find any further information. Helen also wrote lyrics for a song by composer, singer and musician Teresa Del Riego – Little Brown Bird – in 1912. She wrote an article “Why women cannot support the Labour Party” for the Lloyd George Liberal Magazine in June 1921.

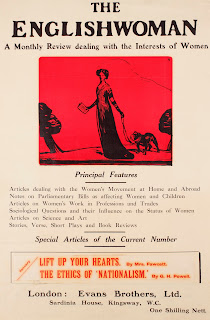

Helen Margaret Nightingale wrote for The Englishwoman

Helen was not in paid employment and “no occupation” is recorded in her

details on the 1911 Census. Then, during the First World War Helen, who was

still living at 47 West Side, Wandsworth Common with her family, served with

the Red Cross General Service Section as a General Service Clerk at the Third

London General Hospital. The hospital was housed in the repurposed Royal Victoria

Patriotic School in Wandsworth. Built in 1859, the school had originally been

an orphanage for soldiers, sailors’ and marines’ daughters.

Helen was one of a number of women sent to replace RAMC orderlies. She

worked at the hospital from August 1915 until summer 1919, starting in the Post

Office, and then transferring to the Main Hall where convoys were received. Susan

Croft notes that many of the poems in a collection published after Helen’s

death include references to hospital work, and were originally published in the

Gazette of the 3rd London General Hospital.

In fact, Helen wrote many articles and poems for the Gazette, and

seems to have contributed to almost every issue. She also wrote a series of “memoirs”

of her time there in the March, April and May 1919 issues as the Hospital

prepared to close down. In the final issue of the Gazette in July 1919,

her poem The War Years appeared on the front page. The poem mourns lost friends

and the “gay and gallant dead”, but views the years of service at the hospital

and the friendships formed there as “Years of Blessed Memory” (Gazette of

the 3rd London General Hospital, Issue Vol. IV.No.10 (July 1919).

After the war, Helen Margaret Nightingale went back to her home and “no

occupation” (1921 Census) at 47 West Side. She died on 14 October 1921, of

heart disease, aged only thirty eight. Her family continued to live at 47 West

Side; her brother Frederick Bayliss, who had become an architect, died there in

1959.

Helen’s writing in the Gazette of the 3rd London General Hospital reflects a lively personality, and I can’t help wondering if she kept a diary or wrote copious letters – as writers tend to do. It would be lovely to know more about her. Who knows, perhaps one day some papers will turn up? In the meantime, I’ll be on the lookout for her novel, Savile Gilchrist MD, though so far I’ve been unable to track down a copy.

Picture Credits:-

AFL Badge and Englishwoman Cover - Women's Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Comments

Post a Comment