In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, bare knuckle boxing was one of Britain's most popular sports. It had its own slang: it was the world of the Fancy, of milling coves and prime goods, bucks and novices, gluttons and swells. This distinctive and racy slang has influenced many writers, as I described in a talk at the Hawkesbury Upton Litfest's Festival of Words on Saturday 22 April 2023. This is a transcript of the talk.

The Game Chicken awakened in Miss Nipper some considerable astonishment; for, having been defeated by the Larkey Boy, his visage was in a state of such great dilapidation, as to be hardly presentable in society with comfort to the beholders. The Chicken himself attributed this punishment to his having had the misfortune to get into Chancery early in the proceedings, when he was severely fibbed by the Larkey one, and heavily grassed. But it appeared from the published records of that great contest that the Larkey Boy had had it all his own way from the beginning, and that the Chicken had been tapped, and bunged, and had received pepper, and had been made groggy, and had come up piping, and had endured a complication of similar strange inconveniences, until he had been gone into and finished.

This possibly baffling paragraph is from Dombey and Sons by Charles Dickens. Miss Nipper is Florence Dombey’s maid, and the man described as the Game Chicken is the constant companion of the young sporting gentleman, Mr Toots, who he instructs in the Science – that is, pugilism. Or, as Dickens puts it, the Game Chicken “knocked Mr Toots about the head three times a week, for the small consideration of ten and six per visit”.

Dickens’s description of the match between the Game Chicken and the Larkey Boy is typical of his exuberant prose style, his relish for language, and his love of words. But the words he uses – tapped, bunged, received pepper – are not his own inventions. The Chicken has been got “into Chancery” early in the fight (which is where a boxer holds his opponent’s head under one arm and punches it liberally with his free fist) He has been fibbed – beaten by a number of fast punches; grassed – knocked to the ground; tapped – hit until his blood ran, as in the phrase tapping the claret, where claret of course means blood; he’s had his eyes bunged up, or shut – if you’d bunged your eye you’d drunk so much your eyes closed; he’s received pepper – he’s had a severe beating. It’s no wonder he’s been made groggy – tottering and weak from the fight – and come up piping – panting or wheezing.

These are all contemporary slang words, and they are all associated with boxing, or pugilism. But where did Dickens get them from?

Slang, and sporting slang in particular, was extremely popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The young buck around town – the dandies, men of fashion, and sportsmen – prided himself on his knowledge of sporting terms, and the often brutal and cruel sports that came with them. In its turn, this slang had its origin in cant – the secret language of criminals. There was a whole genre of books devoted to exposing the secret language and tricks of the thieving crew to the unwary. In the sixteenth century Robert Green published The Complete Cony-Catching, a guide written he said, “for the general benefit of all Gentlemen, Citizens, Aprentises, Countrey Farmers and yeomen, that may hap to fall into the company of such cosening companions”. Greene warns his readers against cony catchers (swindlers); priggers (horse thieves); and foists (pickpockets).

In 1793 James Caulfield published another slang dictionary: Blackguardiana, or a dictionary of rogues, bawds, pimps, whores, pickpockets, shoplifters. Illustrated with eighteen portraits of the most remarkable professors in every species of villainy. Caulfield based his definitions of cant terms on earlier works from the seventeenth century. By now many of these terms were in regular use, although they weren’t included in ordinary dictionaries, and so his book, he said, was intended for the use of foreigners, and also of provincials – those unlucky souls who didn’t live in London.

|

| The 1811 fight between Tom Molyneux and Tom Cribb |

What he didn’t include, said Caulfield, were the rude words all the other slang dictionaries included. I suppose it depends what words you think are rude – he wasn’t shy of the word “bum”. But he may well have had in mind the most well-known of the slang dictionaries, and one on which his own work was based, Francis Grose’s A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, which contains lots of very rude words – although in later editions Grose edited out many of them. In his 1796 edition, for example, he says he removed or toned down “indelicate” words, so the dictionary is “now as little offensive to decency as the nature of it would admit”. Well, the nature of it still admitted a fair amount of indecency, and if, like the Prince Regent in Blackadder, you think dictionaries are good for looking up rude words, then I’d recommend Grose to you.

Grose’s dictionary was first published in 1785. It was immensely popular and ran to many editions. It was the first dictionary to include not only the language of the criminal underworld, but words in every day use, such as drinking and sporting slang. You’ll find many of the words Dickens uses in Grose. Here’s Grose’s definition of to fib, with an example of its usage. “To Fib: To beat.” And the example: “Fib the cove’s quarron in the rumpad for the lour in his bung”.

So I hope that’s made it clearer…

Well, it means “beat the fellow in the highways for the money in his purse.” Grose also notes that fib is a cant term meaning “a tiny lie.”

Francis Grose and his assistant walked the streets of London at night picking up slang words. We know that Charles Dickens also was a great night walker, and it’s hard not to imagine him too keeping his ears open for the language of the streets. Many of his night excursions were taken in the company of police officers, who escorted him into criminal dens and lodging houses. The police themselves were well versed in the language of the criminal classes. We also know that Dickens went to boxing matches.

I don’t know if Dickens consulted Grose, or any of the other slang dictionaries, but there’s no doubt they were available to him, and I think it’s very likely he did. But we do know that one of the influences on his work, and especially on his use of boxing slang, was Pierce Egan.

Pierce Egan was a sporting journalist and a writer. He was born in London, but his family was Irish. He started his life in the printing trade, as a compositor, but he achieved fame with his tales of three rakish young men about town: Corinthian Tom, Jerry Hawthorne and Bob Logic, in Life in London, which follows the three men on their sprees in the drinking dens, docks, boxing and fencing clubs, theatres, and streets of the capital. Egan published two sporting newspapers, and is credited with inventing modern sports reporting. He also edited an edition of Francis Grose’s Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue in 1823.

Egan loved boxing, and he loved the language of boxing, with its slang and nicknames. He uses this language to great effect in his book, Boxiana: or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism. Dickens’s Dombey and Son gives us the Larkey Boy, the Game Chicken, and the Nobby Shropshire One. Egan writes about real life pugilists Delforce the Cudgeller, Marshal the Jawbreaker, and Jack Fearby, the Young Ruffian.

This is from Egan’s report of an 1801 fight between Bristol champion Jem Belcher and Joe Bourke of Wem, Shropshire.

“Second, third and fourth round: Blows were the leading features in these rounds. Science was not displayed by either of the combatants.

Thirteenth round: Milling was the signal, and this round displayed a fine specimen of their talents for hammering. The best round in the fight.”

Jack Fearby, the Young Ruffian, met Belcher in 1803:-

Third round: Much science displayed on both sides – blows reciprocally given and stopped – when Belcher fighting half-armed, and following up his adversary close, the Ruffian fell.

Seventh: Milling on both sides. Ten to one on Belcher.

Eighth: …Fearby rallied with good spirit, and made a hit at Belcher, which he parried with great neatness; and in return, cut the Ruffian’s lips severely. Fearby still game, gave Jem a sharp touch, but did not fetch the claret. Odds reduced five to one.”

|

| An 18th-century pug: Richard Humphreys |

Science, milling, game, hits upon the nob, the Fancy – fancy means the followers or fans of boxing, or any other sport; levellers, facers, hits in the bread-basket – that’s the stomach – Egan’s prose is peppered, like Dickens’s Game Chicken, with boxing slang.

There’s some debate about how much influence Egan had on Dickens. Some think Dickens was such a great genius he couldn’t possibly have been influenced by a second-rater like Egan. But other critics have pointed to the many points of similarity between their work: some of the settings, characters, and episodes, or the fact that Dickens followed Egan’s example and published much of his work in serial form, as well as using illustrations.

Even if Egan was not a direct influence on Dickens, it was Egan who popularised a genre of fiction lively with slang, comic descriptions, grotesque characters, and the contrasts of high and low life, a genre that Dickens developed in The Pickwick Papers. One reviewer write that The Pickwick Papers were “made up of two pounds of Smollett, three ounces of Sterne, a handful of Hooke, a dash of grammatical Pierce Egan”.

Egan also gave us the Game Chicken – because there was, in fact, a real life boxer known as the Game Chicken. He was Henry or Hen Pearce of Bristol, and champion of England – who features in my first Dan Foster novel, Bloodie Bones. To Egan, Pearce was a hero, a man with “a fine athletic form, strength, wind, and agility…with the most manly courage and sublime feeling…for game or bottom [so] unquestionably unrivalled, that this noble and daring spirit never drooped to cry ENOUGH!” Not only was Pearce a great boxer, he snatched a maid from a blazing house in Bristol, and he single-handedly fought off three men who set upon a woman on the Bristol Downs.

But Dickens’s Game Chicken is nothing like the real boxing hero Hen Pearce, and Dickens has been criticised for linking Pearce’s honourable name with Mr Toots’s thuggish boxing coach. P G Wodehouse was one of his critics. Wodehouse wrote in his essay 'The Pugilist in Fiction' that Dickens’s Game Chicken is “a poor, weak-kneed caricature of his class…The great Henry Pearce was also called the Chicken. But there the resemblance stops. Dickens’s Chicken cannot by any stretch of the imagination be taken to represent his profession as a whole. Some few of the scum of the boxing world may have been like him, but not many, while the best, and even the average pugilist, was a different man altogether.”

Wodehouse wrote about boxers in many of his own stories. In his schoolboy story The White Feather he gives us the classic tale of a weedy young boy transformed by learning to box. Bertie Wooster’s friend The Reverend Harold ‘Stinker’ Pinker boxed for Oxford. Wodehouse knew the language of boxing, and to my mind he’s one of the writers who has used it more effectively than anyone. Who else but Wodehouse could have written this:-

“Unseen, in the background, Fate was quietly slipping the lead into the boxing-glove.”

Byron was a poet and a pugilist, and he wasn’t averse to combining the two in his work. The Sultan’s sons in 'Don Juan' “died all game and bottom”. We’ve just heard the words game and bottom used of boxer Hen Pearce. Game means to be full of pluck, fight or spirit; and bottom is, in Grose’s definition, “strength and spirits to support fatigue”. Both these are qualities attributed to the best pugilists. When Don Juan shoots Tom the highwayman, the language is pure slang: “Poor Tom was once a kiddy upon town,/A thorough varmint, and a real swell,/ Full flash, all fancy, until fairly diddled,/His pockets first and then his body riddled.”

A kiddy is a young thief. A swell is someone who’s fashionably dressed. A fancy is, as already mentioned, someone who follows boxing, or other sports. Diddled is cheated. A flash is a thief, or criminal; you may have heard the term flash houses, which were houses or taverns where criminals were known to associate. Flash also means a showy person. And to be flash is to be in the know. Finally, flash means cant, the slang language itself – the Flash Lingo as Grose calls it.

Byron uses more Flash to describe Tom:

Who in a row like Tom could lead the van,

Booze in the ken, or at the spellken hustle?

Who queer a flat? Who (spite of Bow Street’s ban)

On the high toby-spice so flash the muzzle?

Who on a lark, with black-eyed Sal (his blowing),

So prime, so swell, so nutty, and so knowing?

Ken means house; spellken is a theatre; to queer is to puzzle or confound, and a flat is someone who’s been cheated; “toby” means to rob a man on the highway. Tom is “prime”, writes the poet, and “prime” is a word often used of boxers, as in “a prime bit of stuff”, or “prime milling coves”.

Conan Doyle wrote two boxing stories, Rodney Stone and The Croxley Master. Sherlock Holmes is a bare knuckle fighter who once gave the prize fighter McMurdo a “cross-hit…under the jaw” and who might, according to McMurdo “ have aimed high, if [he] had joined the fancy.”

George Bernard Shaw wrote a novel about a prize-fighter: Cashel Byron’s Profession. In this book two women discuss his puzzling declaration that he is “a professional pug”:-

“Lydia rose patiently and went to the bookcase. “You have a cousin at one of the universities, have you not?” she said, seeking along the shelf for a volume.

“Yes,” replied Alice, speaking very sweetly to atone for her want of amiability on the previous subject.

“Then perhaps you know something of university slang?”

“I never allow him to talk slang to me,” said Alice, quickly.

“You may dictate modes of expression to a single man, perhaps, but not to a whole university,” said Lydia, with a quiet scorn that brought unexpected tears to Alice’s eyes. “Do you know what a pug is?”

“A pug!” said Alice, vacantly. “No; I have heard of a bulldog—a proctor’s bulldog, but never a pug.”

“I must try my slang dictionary,” said Lydia, taking down a book and opening it. “Here it is. ‘Pug—a fighting man’s idea of the contracted word to be produced from pugilist.’ What an extraordinary definition! A fighting man’s idea of a contraction! Why should a man have a special idea of a contraction when he is fighting; or why should he think of such a thing at all under such circumstances? Perhaps ‘fighting man’ is slang too. No; it is not given here. Either I mistook the word, or it has some signification unknown to the compiler of my dictionary.”

“It seems quite plain to me,” said Alice. “Pug means pugilist.”

“But pugilism is boxing; it is not a profession. I suppose all men are more or less pugilists. I want a sense of the word in which it denotes a calling or occupation of some kind. I fancy it means a demonstrator of anatomy. However, it does not matter.”

It’s interesting here to see how this slang is something men use - women are excluded from this language.

According to Wodehouse, Shaw once commented “that the popular English novel is nothing less than a gospel of pugilism”. You’ll find references to boxing, and the language of boxing, in many other writers you might not think of associating with it: Anne Bronte uses the expression “come up to scratch” in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. The scratch is the line chalked in the middle of the ring boxers had to come up to at the start of a round or after a knock down or else be counted out.

Once, as the scene from Cashel Byron’s Profession suggests, slang was considered low and disreputable. Dickens may have been happy to use it in his early days, but when one reviewer referred to him as the “Regius Professor of Slang” it no longer fitted his image of himself as a literary figure, and in late editions of Oliver Twist, he edited out much of the slang.

But today many expressions taken from boxing are in common use. Come up to scratch, throw in the towel, saved by the bell, hit below the belt, roll with the punches, glutton for punishment…they are all from boxing. So let’s take the last word from one of the boxing songs quoted by Pierce Egan in Boxiana. These songs were written to be sung at “Convivial Meetings of the Fancy”, and this one was for a dinner given for England champion Tom Cribb.

Come list ye all ye fighting Gills,

And coves of boxing note, sirs,

Whilst I relate some bloody Mills,

In our time have been fought, sirs,

Whoe’er saw Ben and Tom display,

Could tell a pretty story,

The milling-bout they got that day,

Sent both ding-dong to glory.”

Picture Credits

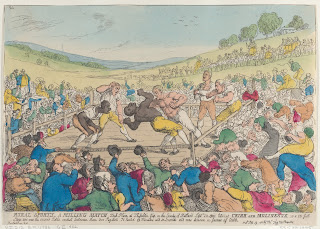

‘Rural Sports, A Milling Match’, September 29, 1811, Thomas Rowlandson, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

‘Richard Humphreys, the Boxer’, John Hoppner, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Comments

Post a Comment