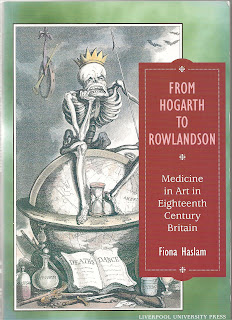

From Hogarth to Rowlandson: Medicine in Art in Eighteenth Century Britain, Fiona Haslam, (Liverpool University Press, 1996)

I’m often asked

about how I go about doing the research for my historical novels. One of the

sources I usually mention is visual art. I’ve always found that looking at contemporary

paintings, prints, sketches, sculpture and so on reveals a wealth of

information about how people of the past lived – what they wore, what sort of

houses they lived in, how they spent their time, the towns and villages they

inhabited. Going to an art gallery is one of my favourite research trips – especially

if there’s a decent café with tea and cake at the end of an afternoon’s study!

Of course, you don’t always have to take artistic representations literally. It’s obvious that whatever you’re looking at is an interpretation of the reality: it’s how the artist saw it. In fact, this subjectivity can be a real advantage if you’re looking for ideas about how people lived and thought. Often the most exaggerated representations, such as satirical prints or caricature, are the most revealing, telling us things that a more serious (or good natured?) work may not. Many of Rowlandson’s prints depict activities that more reputable artists avoided – I don’t mean just his pornographic works, though there are plenty of these and very unpleasant some of them are – but people at their sports, drinking, flirting…

So I was intrigued when I came across Fiona Haslam’s From Hogarth to

Rowlandson: Medicine in Art in Eighteenth Century Britain. Medicine is something

we all of us come into contact with at various points in our lives, and it’s a

place where our experiences and those of our ancestors can meet. Luckily for

us, though, not too closely. While the experiences of pain, illness, fear, and

anxiety in the face of mortality are shared, our medical systems are vastly different.

That’s one reason I’ve never understood anyone who says they would like

to have lived in the eighteenth century. I imagine they’re picturing some Jane

Austenish world of frocks, drawing rooms, tea in china cups, and elegant dances

at assembly rooms. Even if this were to be my lot as an eighteenth woman (though

it very likely wouldn’t be – it wasn’t for the majority of women), the idea of submitting

to medical care based on shaky ground such as the theory of the four humours; of

facing operations and other procedures without anaesthetic or effective pain

killers; or of relying on home remedies based on ingredients like baked earthworms

(jaundice) or hog dung (nose bleeds) does not appeal. Add to that professional

medical regimes heavily dependent on blood letting, clysters, and purgatives, and

I can safely say that no, I would not have liked to live in the eighteenth century!

Many professional medical practices are described in From Hogarth to Rowlandson, which combines historical and social context with an analysis of the artists’ works. Hogarth’s prints are dense with imagery, not all of which is easy to understand. What are those things hanging on the quack doctor’s wall in Marriage-a-la-Mode III: The Inspection? Why are they there and what are they telling us? This book sets out to provide some answers, and very illuminating ones they are. I felt they deepened and enhanced my understanding of the images.

|

| No, I would not like to live in the 18th century! Thomas Rowlandson, The Amputation |

Occasionally, however, those answers are mistaken, as other reviewers

have pointed out. For example, an object Haslam describes as a crutch in Thomas

Rowlandson’s The Amputation is a wooden leg. Confusingly, too,

two of the images have their titles transposed so that a print by Hogarth is

described as Calcar’s Anatomical Lesson and vice versa. Other issues are

that some of the images in the paperback are too small, all are in black and

white, and the author also mentions some works that are not illustrated at all.

However, I found most of the images on line – although sometimes under

different titles from the ones used in the book, which was confusing at times. I

was able to consult these as I read the text, and also very usefully enlarge or

zoom in on various details.

Nevertheless, I really enjoyed From Hogarth to Rowlandson: Medicine in Art in Eighteenth Century Britain. It showed me new ways of looking at images and really paying attention to the detail. In this way, the book helped to increase not only what I can learn from the images, but my enjoyment of them too.

I'll be talking about 'Writing and Researching Historical Fiction and Non-Fiction' at Bishopston Library, Gloucester Road, Bristol, BS7 8BN, on Tuesday 25 April 2023, 7.30 pm to 9.00 pm (includes break). The event is organised by the Friends of Bishopston Library to celebrate World Book Night (23 April 2023). Tickets £3. For more information and booking see Eventbrite.

Picture Credit:-

The Amputation, Thomas Rowland, 1785, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959, Metropolitan Museum of Art (public domain)

Comments

Post a Comment