Mrs Fischer’s War tells the story of a married couple, Carl and Janet Fischer, during the First World War. Carl was born in Germany but to escape a stern father and the restrictions of German life, including the obligation to serve in the army, he settled in England as a young man. Here he has a successful business and has prospered. Janet is English, and adores her husband. They have a thoroughly English son, John. Life for the family is good: comfortable, loving, and full of shared interests.

Carl’s passion for England makes him “more English

than any Englishman”. Then the discovery of his grandmother’s diary

awakens in him the desire to see the town where she and his family lived. He

and Janet plan a camping holiday in Germany. It gets off to a bad start when

John sprains his ankle and is unable to go with them. And, too, there are the rumours

of war. But Janet’s sister offers to look after John, they shrug off the

rumours, and off they go.

At first everything about the holiday is lovely: the countryside, the

friendly people, the clean and welcoming hotels. And then the war starts, and

all at once they are joining the last-minute panic to get out of Germany. Disaster

strikes and they are separated, and not only by circumstances, for Carl’s

allegiance to his Fatherland has reawakened and he decides he owes it to his

country to fight for it. John, meanwhile, decides he owes it to his

country to fight for it. And so Mrs Fischer has a son in the British army, and

a husband in the German. Her friends and acquaintances turn against her, regarding her as the

wife of a German spy and probably a spy herself…and so the tragedy begins.

It was a tragedy faced by many of those designated “enemy aliens” – around 56,000

Germans, as well as Austrians and Hungarians, who were living in Britain when

the war started. Many of them were

naturalised British citizens, and had British spouses. They had lived and

worked in Britain for years, decades in some cases. Overnight they found

themselves thrown out of their jobs and homes, the men interned in camps around

the country, the wives and children left to fend for themselves without the

family breadwinner. Their movements and occupations were restricted, and they

were required to register with the police. English women like Mrs Fischer who

married German men lost their nationality. It was not restored even if they

were widowed or divorced, and they too were required to register, and were

treated as the enemy.

It is a remarkable

novel, and a fascinating exploration of patriotism (“a frightening thing”)

and national identity. It tells of how a civilised nation becomes a nation of

barbarians – to others, that is, never to themselves; how fear and hatred march

hand in hand, and vicars preach war from the pulpit; anonymous letters lose you

your job; and the people who smiled at you yesterday look away and “cross to

the other side of the road” today.

Henrietta Leslie (1884-1946) experienced much of this

herself. Her real name was Gladys Schütze,

née Raphael, and she was born into a Jewish family in London. After her first

marriage ended in divorce (she published two novels under her first married

name, Gladys Mendl), she married Harrie Leslie Hugo Schütze (1882–1946)

in 1913. He had been born in Australia

and was a bacteriologist at the Lister Institute in London.

Before the war, Gladys was a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union. When Mrs Pankhurst, who had been sentenced to three years’ penal servitude, was out of prison on licence she stayed with the Schützes in their house in Glebe Place, Chelsea. She addressed a meeting from their balcony on 21 February 1914, and police attempts to arrest her were thwarted by her “bodyguard” wielding clubs. The next day, once again protected by her “bodyguard”, she escaped from Glebe Place before the police could rearrest her.

After the April 1913

raid on WSPU headquarters, the Information Department was run from Glebe Place,

but had been removed by June 1914, when the police raided the house. In addition, Gladys carried messages

to Christabel Pankhurst in Paris, where the WSPU leader fled after the 1913

police raid. She also took part in the deputation to Buckingham

Palace on 21 May 1914, and was injured during struggles with the police.

During the First World War Gladys was a pacifist, and a member of the Suffragettes of the WSPU, a break-away group from Mrs Pankhurst’s pro-war and jingoist WSPU. Because of her German name she suffered discrimination and was forced to leave the Society of Women Journalists and the Literary Club. From 1916 she used the pen name Henrietta Leslie, and wrote over twenty novels, as well as plays, an autobiography and travel books.

|

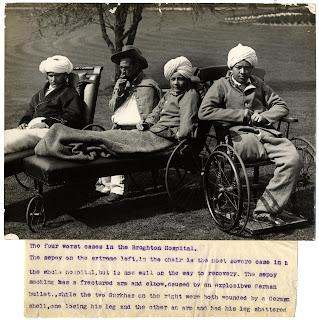

| "bluff as you will, the blind won’t see, nor the lame walk...": amputees at the military hospital, Brighton |

In 1920 she became a journalist on the socialist Weekly Herald and

later the Daily Herald. She left the Herald in 1923 and became an

organiser for the Save the Children Fund. In 1928 she travelled to Bulgaria to

report on the situation after an earthquake. She was also a member of PEN.

Gladys joined the Church of England in 1923 but events in Germany in the

1930s led to her reaffirmation of her Jewish identity in solidarity with Jews

there, and she assisted many refugees from Nazi Germany. She reluctantly

relinquished her pacifist beliefs in the face of the threat of Fascism and

resigned from the Peace Pledge Union. The Schützes were in America when the

Second World War started, and returned to England. Gladys died in hospital in

Bern, Switzerland, in 1946, and Dr Schütze

died three weeks later.

Mrs Fischer’s War is a moving account of the suffering caused by war from a point of view not often described: the “enemy” in our midst. The Fischers’ transformation from a well-liked and respected couple to pariahs is one more example, if any were needed, of the madness of war. The novel is a powerful reminder that what war has broken can never be mended: “Bustle as you will, bluff as you will, the blind won’t see, nor the lame walk, nor the unborn come to life, nor cold dead lips press warm kisses on the mouths of those that loved them. Dead – vanished – gone – everywhere waste.”

Waste indeed, and I shall certainly be trying to find more books by Henrietta Leslie, who seems to have been a very interesting writer.

Picture Credit:-

'The four worst cases in the Brighton hospital,' 1915. Photographer: H D Girdwood. From the Girdwood Collection held by the British Library; British Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Comments

Post a Comment