Julia Prima, Alison Morton (Pulcheria Press, 2022)

Alison Morton is the inventor of Roma Nova, a small but influential state (about the size of Luxembourg) founded in AD395 by 400 Romans led by Senator Apulius and his daughters. Apulius, his daughters and the people who followed him had seceded from the Roman Empire when their freedom to worship Rome’s traditional, pagan gods was obliterated by the new official religion of Rome, Christianity. Alison Morton has written nine thrillers about modern-day Roma Nova, which has developed over the centuries into a state which has retained many Roman republican qualities – the Roman gods are still worshipped – but where women have come to wield real political and social power.

It's a fascinating and well-developed alternative history, and in Julia

Prima Alison Morton takes the reader back to the beginning and gives us the

story of Apulius and his wife, Julia. From the minute they set eyes on one

another it’s a tale of stormy passions and unconquerable love. Separated, as in

all good romances lovers must be, they have to overcome heartache and hardship,

distance and danger before they can be reunited.

For me, it was what separated the pair that held the greatest interest –

the clash between paganism and Christianity. As the author explains in her historical

notes at the end of the novel, Julia’s problem is that she is trapped between

Roman and Christian law. Under the first she’s legally divorced from her first,

unpleasant and Christian husband. Under the second she is still considered to

be his wife, and so she cannot remarry for fear of causing offence to the

Christians and thus jeopardising her family’s position. It is only by removing

herself from the influence of the local bishop, Eligius, that she dare

contemplate remarriage.

The struggle between paganism and Christianity is a subject that’s fascinated

me for a long time, and so I was interested to see how it’s handled in Julia

Prima. Here, there’s a real sense of the persecution pagans suffered as

their religious practices were stamped out by increasingly harsh laws and the

devastating intolerance of many of the founders of the Christian church, which

had nothing to do with the teaching of Christ. What it did have a lot to do

with, or at least so the novel suggests, was power.

Christianity is portrayed as a stepping stone to political and social

influence. Bishop Eligius wields political power and cultivates influental

people, all the way up to the Emperor. Julia’s father publicly attends

Christian services while privately adhering to his own faith, in order to

maintain his position as leader of his province. Soldiers become Christians

because not doing so means the loss of rank, as Apulius discovers to his cost. To

these characters, Christianity is a religion of expediency; it’s what they have

to do if they want to get on. It’s also increasingly a religion of safety as

the Christians grow in power and influence, and persecution intensifies. People

“mumble their [the Christians’] prayers and do what’s necessary” in order to

survive. In Julia Prima, the author makes their predicament real and

personal; the history comes alive.

And it is very lively! The story evolves into a journey narrative, and what an exciting journey it is, with shadowy pursuers, attacking bandits, fights and disguises. All in all, the premise is intriguing, the characters well drawn, and the setting very well realised indeed. I really felt as if I was on that journey with Julia and her two faithful servants – both appealing characters in their own right – experiencing the heat and the dust, the dangers, the horrible food, the adrenalin rush of the fights. A perfect read for us armchair adventurers who wouldn’t know one end of a gladius from the other!

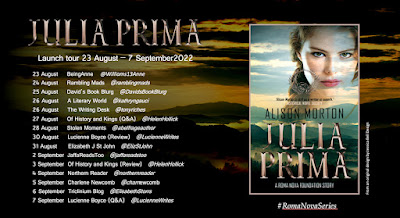

Alison will be joining me in my next blog on 7 September 2022 to talk about Romans, writing about distant times and places, and more. In the meantime, you can catch up with her on her blog tour.

Goodness, that's a comprehensive and insightful review! Thank you, Lucienne. We hear a great deal about the persecution of Christians, but very little about the other end of the tunnel – the repression against those continuing to worship the old gods. This division split families and created turmoil at a time full of other pressures. Eventually, in order to have a peaceful life, people went along with it.

ReplyDelete