This is an extended version of a talk given at the Crime, Thriller and Mystery Books event, Hawkesbury Upton Literary Festival, 30 April 2022.

This is a "long read" and if you prefer to download and read it, there is a pdf version on my website here .

“How are you this morning, Betteredge?” asked Franklin Blake.

“Very poorly, sir,” answered Gabriel Betteredge.

“Sorry to hear it. What do you complain of?”

“I complain of a new disease, Mr. Franklin, of my own inventing. I don’t want to alarm you, but you’re certain to catch it before the morning is out.”

“The devil I am!”

“Do you feel an uncomfortable heat at the pit of your

stomach, sir? and a nasty thumping at the top of your head? Ah! not yet? It

will lay hold of you…, Mr. Franklin. I call it the detective-fever; and I

first caught it in the company of Sergeant Cuff.”

Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone

The new disease of

Detective Fever was first diagnosed by Wilkie Collins in his novel, The

Moonstone – and I think readers have been suffering from it ever since.

The Moonstone was originally

published in serial form by Collins’s great friend, Charles Dickens, in his

magazine All the Year Round between January and August 1868. Later that

year, the novel was published in three volumes [1]. It was later

published in one volume, and this is how we read it today.

The Moonstone was an instant

best seller, and it is credited with being the first detective novel.

In fact, there

were earlier stories featuring detection. Edgar Allan Poe’s 1841 Murders in

the Rue Morgue pre-dates The Moonstone by twenty seven years and is

often said to be the first true detective story. In this tale, Poe also

introduced the classic locked-room mystery. But this is a short story, not a

novel.

Other early

Victorian novels also had a detection theme. Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1848 Mary

Barton includes a character who investigates a murder. In Mary Elizabeth

Braddon’s 1862 Lady Audley’s Secret a man investigates his friend’s

disappearance. In addition, many detective stories from America and Australia

were published in Britain, as well as translations of French stories.

Possibly the most serious rival to The Moonstone for position as the first detective novel is The Notting Hill Mystery by Charles Warren Adams, serialised between 1862 and 1863 [2]. In this tale, the narrator carries out an investigation using chemical analysis, interviews with witnesses and a crime scene map [3].

|

| Detective stories were popular with Victorian readers |

Michael Sims in

his introduction to The Dead Witness: A Connoisseur’s Collection of

Victorian Detective Stories (2011) traces the detective story back

further still. The Hebrew prophet Daniel turns his hand to detection when he is

called upon by King Cyrus to investigate nocturnal goings-on in the god Bel’s

sanctum. Every night the priests leave food and drink for Bel, and every

morning the food and drink have been consumed. Cyrus believes this proves that

Bel is not simply a clay idol. Daniel proves otherwise by setting a trap worthy

of Sherlock Holmes. He scatters ash on the floor of the sanctum before the door

is locked for the night as usual. In the morning the ash reveals footprints.

When questioned, the priests confess they have been lying and there is a secret

door through which they enter the sanctum at night in order to take the

offerings.

This also, by the

way, puts Daniel centuries ahead of Poe in solving a locked-room mystery.

Collins himself

had already written a number of stories featuring detection before The

Moonstone. In The Diary of Ann Rodway (1856) an impoverished London

seamstress investigates the murder of her friend. Most famously, The Woman

in White (1860) contains many of the elements found in The Moonstone.

In both books, crimes are committed; in both a narrator sets out to investigate

the crimes by assembling witness statements; and in both the stories are partly

based on real cases.

But The

Moonstone holds a unique place in the development of detective fiction

because in it Collins laid the groundwork for the genre, introducing or

mastering the key elements of a detective story, elements which are still

important today.

But before we

explore those conventions, let’s pause to ask: why the 1860s? Why did the

detective novel appear when it did, in the middle of Queen Victoria’s reign

(1819-1901)? And why did the detective story appeal to the Victorian

imagination?

The rise of the

detective genre goes hand in hand with the development of the modern police

force. The traditional method of maintaining law and order was based on the

parish constable system. Parish constables were male householders who were

obliged to serve a period as a law officer in their parishes, usually a year.

But increasingly the appointment of men with no training, who often had their

own jobs or businesses, served only for limited periods, and had jurisdiction

only in their own parish boundaries, came to be seen as inefficient. A more

professional and organised service was needed to tackle crime.

Policing was of

particular concern in London because of its larger, more anonymous and more

mobile population, and its high crime rate. In 1828 a Parliamentary Committee

was set up to examine the issue. On its recommendation, the Metropolitan Police

force was set up in 1829 to replace the parish constables.

The new police

force did not extend through the country. Some boroughs were required to form a

police force from 1835 [4], and counties were authorised to have one if they

chose from 1839 [5], but it was not until 1856 that it became mandatory for

every county in England and Wales to have a police force [6].

At first the focus

of the new force was on prevention, rather than detection. Gradually the focus

shifted away from prevention when it was realised that it was not possible to

make a significant difference on the crime rate using preventive methods. In 1842

the Metropolitan Police set up the country’s first Detective Department with

its headquarters at Scotland Yard (it became the Criminal Investigation

Department in 1878.) The word ‘detective’ as in ‘detective police’ entered the

English language for the first time. Later, forces around the country followed

suit and set up their own detective departments.

The new detective

police were glamourous and mysterious figures. Kate Summerscale has suggested

that they were “as magical and marvellous as the other marvels of the 1840s and

1850s – the camera, the electric telegraph and the railway train” [7]. Their

exploits were reported in the newspapers and avidly read by a fascinated

public. In the 1850s, pseudo-memoirs – fictional detectives’ autobiographies–

were popular, and further fed this interest. Examples include Recollections

of a Police Officer by William Russell, published in Chambers’s Journal

between 1849 and 1853 and later as books; and The Detective’s Notebook

by Charles Martel (Thomas Delft), 1860. Magazines began to publish short

stories about the police; and new, cheaper publications appeared targetted at a

mass, working-class readership, spreading the fame of the police further.

Detective stories caught on.

So now let’s look

at what it is that makes The Moonstone such an influential novel in the

development of detective fiction. First of all, we need to ask, what is a

detective novel?

A detective novel

is distinct from a mystery novel. In a detective story, a crime must be

committed, and the action must revolve around the solution of the crime. So

there must be at least one central character who is a detective, and whose

business it is to solve the crime.

But the detective

does not have to be a police detective. In fact, fictional stories featuring

private detectives became much more popular than stories featuring official

police. It’s not hard to see why: private detectives aren’t hemmed in by police

rules and regulations. They can be as eccentric as they like, as unorthodox as

they like, and they can even be as unlawful as they like.

They don’t have to

be professionals who earn their living as investigators. They might even be

accidental detectives, called upon to investigate a crime for personal reasons,

such as to protect a family member; or avenge a friend, like Collins’s Anne

Rodway, or to clear themselves if they’ve been falsely accused; or to help

someone recover stolen property without causing a scandal.

They might be

investigators in other fields, such as the insurance agent in The Notting

Hill Mystery. Or they might be linked with crime, such as coroners,

lawyers, or police doctors – like R Austin Freeman’s Dr John Thorndike, who

appeared in the early 1900s.

They can even be

criminals, like Raffles the gentleman thief created by E W Hornung in 1898.

More astonishing

still, they can be women. Stories about female detectives were very popular in

the 1890s. The female detective Loveday Brooke, introduced in 1893 by Catherine

Louisa Pirkis, works in a private detective bureau.

Later still,

Baroness Orczy of Scarlet Pimpernel fame didn’t let the fact that there were no

women in the British police force spoil a good story. In 1910 she wrote about a

woman who works for CID in her stories Lady Molly of Scotland Yard [8].

|

| Dorcas Dene, the female detective created by George R Sims |

In The

Moonstone Collins employs both police and private detectives. Franklin

Blake, a gentleman, drives the investigation, but Collins also introduces the

unforgettable Inspector Cuff. Cuff is based on the real-life detective Jack

Whicher of Scotland Yard. Whicher was one of the original eight detectives who

were recruited into the CID when it was formed in 1842. In 1860 he was in

charge of the notorious case of the Murder at Road Hill House, when sixteen

year old Constance Kent murdered her four year old brother. Collins used many

details from this famous case in The Moonstone [9].

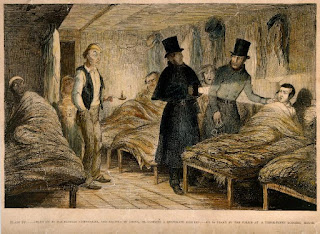

Collins’s friend Charles Dickens also created a detective based on a real detective: Inspector Bucket in Bleak House, modelled on Inspector Charles Field. In fact, Dickens was so fascinated by the police that he spent many nights out and about with them. He describes many of these expeditions, many taken in Field’s company, in his magazine articles, and it’s easy to see from his descriptions where much of the material for his own books came from. One night he accompanied Field and his men to St Giles Rookery, a network of slums and thieves’ dens. London’s police were required to supervise lodging houses and keep a look out for wanted and suspected criminals taking refuge in them [10], and it is one of these raids Dickens describes.

Saint Giles’s church strikes half-past ten. We stoop low, and creep down a precipitous flight of steps into a dark close cellar. There is a fire. There is a long deal table. There are benches. The cellar is full of company, chiefly very young men in various conditions of dirt and raggedness. Some are eating supper. There are no girls or women present. Welcome to Rats’ Castle, gentlemen, and to this company of noted thieves!

…Inspector Field’s is the roving eye that searches every corner of the cellar as he talks. Inspector Field’s hand is the well-known hand that has collared half the people here, and motioned their brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, male and female friends, inexorably to New South Wales. Yet Inspector Field stands in this den, the Sultan of the place. Every thief here cowers before him, like a schoolboy before his school master. All watch him, all answer when addressed, all laugh at his jokes, all seek to propitiate him.

Charles Dickens, ‘On Duty With Inspector Field’, Household Words, 14 June 1851 [11]

|

| Police raid a lodging house |

Like Dickens, Collins studied the police at work. One of his inspirations for The Moonstone was attending a criminal trial in London. Watching how the details of the crime emerged as the witnesses gave their testimony, it struck him that using a series of narratives would work well in his novel.

Both Collins and

Dickens are sympathetic to the police, and their police characters are treated

with respect and admiration. Inspector Cuff in The Moonstone, who fails

to solve the case, may be fallible, but he is not foolish.

Later authors took

a different view. A number of police scandals in the 1880s – the exposure of

corruption in the force, the failure to solve serious crimes, and the perceived

failure to protect the public from terrorism and political crime – led to the

undermining of public faith in the police. This was reflected in fiction which

depicted police officers as slow-witted, plodding, and unimaginative. The most

well known example is, of course, Sherlock Holmes, who first appeared in 1887

and who is always miles ahead of the Scotland Yard detectives. They can’t

compete with his intelligence, knowledge, and superior education, and in fact

they often defer to him and even let him run their investigations.

Unsurprisingly,

Holmes was not popular with real policemen!

|

| Sherlock Holmes |

Other examples of

the superior private detective are Harry Blyth’s Sexton Blake, whose first

story appeared in 1893 [12]; and Martin Hewitt, created by Arthur Morrison in

1894 [13].

But, whatever form

your detective takes, he or she must be a central character in the novel.

Some of the other

tropes Collins uses in The Moonstone are:-

- The country house setting with an assembly of suspects who all have motive, means and opportunity to commit the crime.

- The fair-play rule, meaning that the reader has all the information the detective has. The author doesn’t simply withhold important details – a deeply irritating ploy. This was one of the things for which Dorothy L Sayers praised Collins. She said that in this respect The Moonstone was “impeccable…The Moonstone set the standard and…it has taken us all this time to recognise it” [14].

- The detectives are often eccentric – Inspector Cuff is passionate about roses.

- The criminal is often the least likely suspect. I’ll keep quiet about this one in case you haven’t read The Moonstone!

- There is often a scene reconstructing the crime.

- Suspicion shifts from person to person – and they all have secrets to hide.

- Minute details are important. “I have never met with such a thing as a trifle yet,” declares Inspector Cuff in The Moonstone, who has solved a recent case after noticing an ink spot on a table cloth.

- The

crime does not have to be a murder – and of course in The Moonstone it

is theft.

All of these

tropes will be familiar to anyone who reads detective stories. As Dorothy L

Sayers said, “The Moonstone set the standard.” Indeed, she thought that The

Moonstone was “probably

the finest detective story ever written [15].

The detective

genre continued to grow and expand after The Moonstone. Sherlock Holmes

ushered in the Sherlock Clones – a host of professional or semi-professional

private detectives who detect for other reasons than clearing their own or a

friend’s name. There are disabled detectives – Ernest Bramah’s blind Max

Carrados first appeared in 1914. There are working class detectives, and

aristocratic detectives such as Dorothy L Sayers’s own Lord Peter Wimsey in the

1920s. There are women detectives such as Miss Gladden, created by Andrew

Forrester in The Female Detective (1864), and the nosy aging spinster

Amelia Butterworth, introduced by the American detective fiction writer Anna

Katherine Green in her 1897 novel That Affair Next Door. Amelia

Butterworth is said to have inspired Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple.

There are even occult

detectives, as anyone who has read William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki stories will

tell you. Published in the 1900s, these wonderful stories follow the adventures

of a man who investigates ghostly carryings on.

Clearly, there’s

no end to the ingenuity of our fictional detectives – or their authors.

Detective-fever is here to stay – and I for one am not looking for a cure!

Was the Golden Age of Detective Fiction really golden? In her talk for HULF, Debbie Young explored some of the darker aspects of detective fiction from the inter-war period. Read her fascinating talk on her blog The Golden Age of Detective Fiction

Notes

[1] It was published in three volumes by Tinsley Brothers in July 1868.

[2] The Notting Hill Mystery was serialised in eight parts in Once a Week under Charles Warren Adams’s pen name, Charles Felix, and published as a novel in 1865. It is now available in the British Library Crime Classics series.

[3] Even earlier was William Godwin’s 1794 novel Things as They Are, or the Adventures of Caleb Williams in which Caleb investigates a murder. Crime narratives had long been popular in the form of Newgate narratives (usually accounts of prisoners’ gallows confessions and repentance), broadsheets, ballads, and news stories about the famous Bow Street Runners and notorious crimes and criminals. Daniel Defoe’s 1722 Moll Flanders is about a con artist and thief transported to America; and also published in 1722, Defoe’s Colonel Jack gave readers a male pick-pocket and thief. Slang dictionaries purporting to reveal the secrets of criminal “canting” crews were also popular. However, the focus in this literature is on the criminal, not the detective.

[4] Municipal Corporations Act 1835.

[5] County Police Acts 1839 and 1840.

[6] County and Borough Police Act 1856. The new forces were not accountable to central government and ran fairly independently.

[7] Kate Summerscale, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher: or the Murder at Road Hill House (2009), (Introduction, p. xx).

[8] There were no women police until the First World War, when the Women’s Police Volunteers acted as auxiliaries to the official police force.

[9] The case is examined in detail in The Suspicions of Mr Whicher: or The Murder at Road Hill House by Kate Summerscale (2009).

[10] Police responsibility to license and supervise lodging houses was imposed by the Common Lodging Houses Act 1851.

[11] Reprinted in The Dead Witness: A Connoisseur’s Collection of Victorian Detective Stories, ed. Michael Sims (2011), pp. 80-98.

[12] The first Sexton Blake story by Harry Blyth, writing as Hal Meredeth, appeared in The Halfpenny Marvel in 1893.

[13] The creation of Arthur Morrison, Hewitt first appeared in the Strand magazine in 1894.

[14] Dorothy L Sayers, Introduction to the Everyman Edition of The Moonstone.

[15] Quoted in https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-the-moonstone#footnote3

Picture Credits

The Rival Detectives,

or Dangerous Ground,

Emma M Murdoch, 1887: British Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Dorcas Dene,

Detective,

George R Sims, 1897: British Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Police

raid a lodging house at night and arrest a convicted thief. Coloured etching by

G Cruikshank, 1848, after himself: Wellcome Collection, Public Domain Mark

Sherlock Holmes, from

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, 1892: British

Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

New Detective Stories, Sir Gilbert Edward Campbell, 1891: British Library on Flickr, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Comments

Post a Comment