I’ve often wondered why owning the signature of someone you admire or are interested in is so appealing. I supposed it is because a signature feels like a part of the person concerned, something produced by their own hand. It can also feel intensely personal if it is dedicated to you, which is why so many people ask authors to write their own names – “to so-and-so” – at a book signing.

|

| Cicely Hamilton's Autograph |

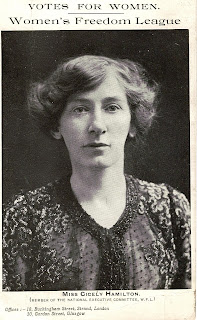

I’ve never collected signatures but I have acquired one or two over the years. Recently I obtained this signature by writer and suffrage campaigner Cicely Hamilton. It was probably sent to someone who had written to her and requested her autograph.

Cicely Hamilton (1872-1952) is one of my favourite authors. A novelist, playwright and actress, she found fame with her 1908 play Diana of Dobson’s. She was a member of the Women’s Freedom League, formed after a split within the WSPU in 1907, and the Actresses’ Franchise League. She also worked with both the WSPU and the non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. She wrote the words to the suffragette anthem The March of the Women, composed by Ethel Smyth, as well as a number of suffrage plays (with Christopher St John) including How the Vote Was Won and A Pageant of Great Women.

|

| Cicely Hamilton, Women's Freedom League |

Her books include Marriage as a Trade, a stringently unromantic exploration of marriage as a means of livelihood for women. She also wrote a number of novels, including Theodore Savage: A Story of the Past or the Future about the collapse of civilisation after war; and a play, The Old Adam, which also explores anti-war themes. She wrote for Time and Tide, and also wrote a series of book based on her travels – Modern Scotland, Modern Germanies and so on.

Autographs were extremely popular in the 1900s, and are still so to this day. They were one of the ways women celebrated and commemorated the friendships they made during the suffrage campaign. Many women carried autograph books in which they asked their famous and not so famous friends to record their signatures. An autograph album which belonged to one of the Redfern sisters contained fifty signatures collected in or around 1909. They included those of Sylvia Pankhurst, Helen Archdale, Sarah Bennett, Hilda Burkitt and Charlotte Despard. Many of the signatories also wrote messages: Kitty Marion’s read, “the greatest enemy to freedom is not the tyrant, but the contented slave”.

Other suffragettes known to have kept autograph books include Olive Wharry (1886-1947) and Grace Marcon. Olive Wharry was an artist and a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union and the Church League for Women’s Suffrage. She spent two months in prison in 1911 for breaking windows and six months for the same offence in 1912. She and Lilian Lenton set fire to the tea house at Kew Gardens in 1913. Grace Marcon (1889-1965) was the daughter of Canon Marcon of Norwich. She served two months in Holloway in 1913, and was sentenced to six months in prison in 1914 for damaging paintings at the National Gallery.

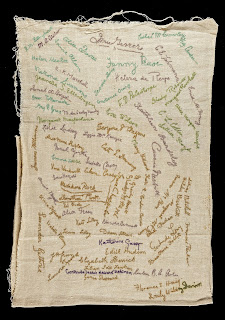

Signatures were also embroidered on cloths or handkerchiefs, which were often made in prison. The Priest House at West Hoathly is the proud owner of a handkerchief signed by sixty six women in Holloway in 1912. The handkerchief was rescued from a bonfire in the 1970s. It is not clear if the needlework was done by the women themselves or one embroideress. The Women’s Library owns a similar cloth signed by many women but embroidered by one person.

|

| Autographs embroidered on a cloth, Women's Library |

Many of the same names appear on both pieces, including Grace Tollemache of Batheaston, Victoria Simmons of Bristol, Vera Wentworth and Janie Terrero. Eighty signatures of women who had been on hunger strike even made it onto a banner carried at a WSPU procession in 1910.

As I can no longer take a book along to a reading and ask Cicely Hamilton to sign it, or thrust an autograph book for suffrage campaigners’ signatures under her nose, her signature on a slip of paper is the next best thing!

For more

on Cicely Hamilton see my blog ‘Spotlight on…Cicely Hamilton’

For

information on the Redfern autograph album see ‘Suffragette autograph album

illuminates movement's struggles’, The Guardian, 6 December 2021 ; and ‘Suffragette Autograph Album To Be

Auctioned: Save It For The Nation – And Future Researchers’, Elizabeth

Crawford, 8 December

2012

For information on the West Hoathly handkerchief see ‘Prison embroidery by Suffragettes, 1905–1914’, Denise Jones, 27 May 2016 ; and ‘The Suffragette Handkerchief at The Priest House, West Hoathly’, www.sussexpast.co.uk

Picture Credits:-

Cicely Hamilton postcard and Cloth With Suffragettes' Names - Women's Library at the LSE, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Comments

Post a Comment